I Understand Why the “Wicked” Novel was Pulled From Schools. “Banning” It Misses the Point

by Chris Peterson

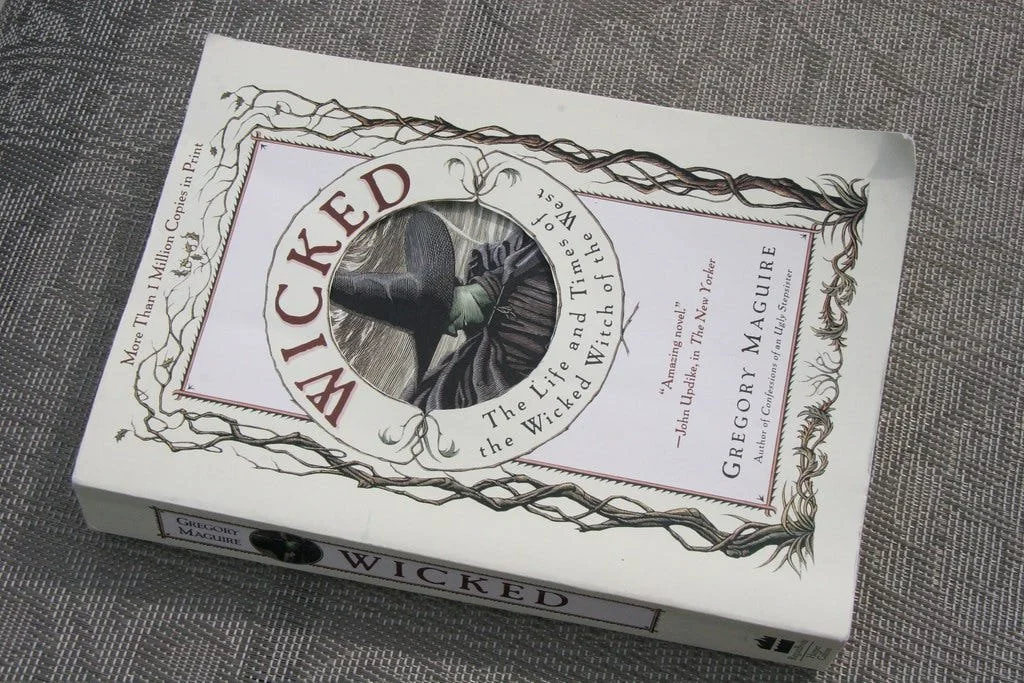

When news broke that Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West had been removed from Utah public school libraries, the reaction was swift and loud. The word doing the most work in the headlines was “banned,” and I’ll admit right up front that I don’t love that framing. It immediately turns a complicated decision into a culture-war flashpoint, flattening any real discussion about age, intent, or content.

But here’s where I think honesty matters: the Wicked novel is not appropriate for young readers.

And that shouldn’t be controversial to say.

This isn’t the Wicked most people know. It’s not the Broadway musical with its soaring ballads and softened edges. Gregory Maguire’s novel is darker, denser, and deliberately unsettling. It includes explicit sexual material, graphic sexual encounters, references to fetishistic behavior, and explorations of sexuality meant to, in my opinion, provoke rather than comfort. There are scenes involving sexual violence, coercion, bodily harm, animal cruelty, drug use, and brutal political repression. These elements aren’t subtle. They’re not merely implied. They’re on the page because Maguire is interrogating power, corruption, and moral decay in a fantasy world that mirrors our own.

That doesn’t make the book bad. In fact, it’s precisely what makes it effective for adult readers. But it does make it inappropriate for a school setting meant to serve children and teenagers at varying stages of development.

So while I resist the language of “banning,” I don’t struggle with the idea that schools should make thoughtful decisions about what belongs on their shelves. Age appropriateness is not censorship. It’s curation. And schools have always curated. They have to.

Where this story becomes more troubling, however, is when Wicked is lumped together with other removed titles under the same sweeping justification. Among them is Nineteen Minutes by Jodi Picoult, and that decision I absolutely disagree with.

Nineteen Minutes is a difficult book, but it is difficult with purpose. It confronts school violence, bullying, masculinity, sexual assault, and the warning signs adults too often miss until it’s too late. It doesn’t sensationalize trauma. It examines it. It asks readers to sit with uncomfortable questions and wrestle with empathy, accountability, and systemic failure. For many young readers, it offers language for experiences they are already navigating, whether we want to admit that or not.

Unlike Wicked, which is explicitly adult in its sexual content and political cynicism, Nineteen Minutes meets young people where they actually are. Removing it from school libraries doesn’t protect students. It deprives them of context, conversation, and tools for understanding a world they are already living in.

And this is why the word “banned” becomes such a blunt and ultimately unhelpful instrument. When vastly different books with vastly different purposes are treated the same way, nuance disappears. We stop talking about audience and intent and start shouting past one another. Everything becomes symbolic. Nothing becomes thoughtful.

I can understand a school district deciding that Wicked belongs in adult spaces. I cannot understand applying the same logic to a novel that has long been used to foster dialogue, reflection, and empathy among teens.

If we’re going to draw lines, they should be drawn carefully. If we’re going to remove books, we should be honest about why. And if we’re going to have this conversation at all, we owe it to readers, students, and educators to be precise with our language.

Not every boundary is a ban. But not every removal is defensible either. And pretending those distinctions don’t matter is how we lose the plot entirely.