Questions Rise as Epstein Files Reference Julie Taymor, “The Lion King”, and NYC Theatre Leaders

by Chris Peterson

On January 30, the U.S. Department of Justice published a massive new batch of Jeffrey Epstein investigative materials as part of its Epstein Library disclosures, adding millions of pages of emails, schedules, and other records to the public archive. Among the names that appear in these documents are New York theatre power players, including Julie Taymor and Jeffrey Horowitz, in entries and correspondence that indicate interactions with Epstein after his very public 2008 conviction.

The references do not allege, or even slightly suggest, criminal wrongdoing by either theatre figure. But they do raise uncomfortable questions about proximity and access. In one instance, the documents describe ticket arrangements connected to The Lion King while Epstein was incarcerated in 2009; in another, correspondence ties Epstein to potential high-dollar fundraising outreach connected to Theatre for a New Audience. The common thread is not scandalous theater-kid gossip. It’s the normal mechanics of influence continuing to function around a man who was already publicly convicted and registered as a sex offender.

As first brought forward by the StageLeftReport on TikTok (which is a great follow, by the way), the Taymor mentions—at least in the documents and excerpts now circulating from the DOJ release—aren’t presented as salacious. They’re presented as normal. The kind of normal New York runs on: introductions, coordination, access, the quiet assumption that if someone is wealthy enough, they remain “worth knowing,” even when the rest of the world has already clocked what they are.

The part that matters here isn’t the cheap little adrenaline rush of seeing theatre names pop up in a government archive like it’s some cursed Playbill insert. It’s the blunt, boring, nauseating question those names force on all of us: why were any of these relationships still continuing after 2008?

Because by then, Jeffrey Epstein wasn’t a “whisper network” situation. He wasn’t some vague rumor floating around the Upper East Side like a bad cologne. He was a convicted sex offender. Public. Documented. Known. The kind of person who should have triggered an immediate, automatic response from any institution that claims to have values: we are done here. Hard stop. No exceptions. No “but he’s complicated.” No “but he’s a patron.” No “but the board will be upset.”

And yet the paper trail we’re looking at suggests something else. It suggests that even after the conviction, the normal rules of consequence didn’t really apply. That people still took the calls, still did the polite logistics, still entertained the idea that he was someone worth dealing with in the language of “opportunities” and “relationships” and “support.” Not because anyone was confused about who he was, but because the question quietly became: what do we get out of keeping him close?

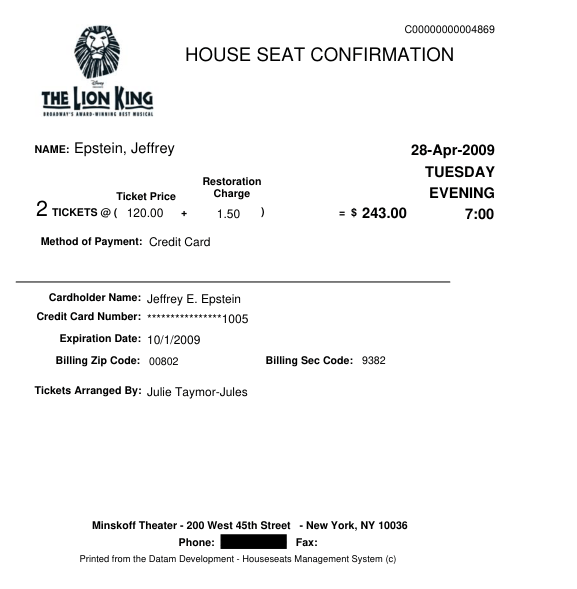

For example: one record circulating from the DOJ release shows ticket arrangements for The Lion King in April 2009, with the tickets “arranged by Julie Taymor-Jules,” tied to Epstein or someone in his orbit. That date matters. At that point, Epstein had already pleaded guilty in 2008 to procuring a minor for prostitution(the victim was reportedly 14 years old) and was serving the sentence that followed. So you’re left with the kind of question that should be easy in a functional moral universe: why is anyone doing favors, arranging access, or smoothing the path for a convicted sex offender at all, no matter how rich he is?

And yes, the choice of show matters too. This isn’t some adults-only after-hours benefit where people can pretend they didn’t think through the optics. This is The Lion King—a child-friendly, family-facing cultural institution. So even if you want to argue “it was just tickets,” the larger point is still sitting there, unblinking: why was he still being treated like a normal member of polite society who deserved normal perks?

And if that’s the baseline in 2009, it makes the next question unavoidable: how many other doors stayed open, how many other calls got returned, and how many other institutions did the same quiet little calculus because the money was tempting and the accountability was optional?

And sorry, but this is where the theatre world needs to stop acting shocked. Because wealth isn’t incidental to how this happens. It’s the whole engine. In New York arts culture, money doesn’t just buy you tickets. It buys you proximity. It buys you the kind of “patron of the arts” treatment that makes people forget what they already know because it’s more convenient to forget. It buys you a seat at the table even when you have no business being in the building.

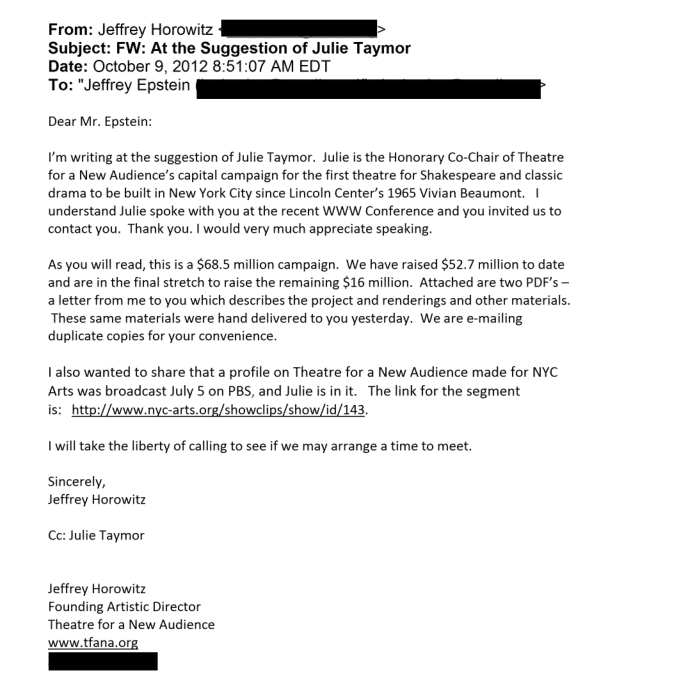

And then there’s the Theatre for a New Audience thread, which is where the question stops being abstract and starts feeling… operational. In a 2012 email chain flagged by readers digging through the DOJ’s newly posted Epstein archive, Jeffrey Horowitz is described as reaching out to Jeffrey Epstein about a potential donation—after being encouraged to do so by Julie Taymor.

The date is the gut-punch. By 2012, Epstein wasn’t just “that guy with rumors.” New York courts had already affirmed his adjudication as a Level 3 sex offender under the state’s Sex Offender Registration Act (that order was entered in 2011 and corrected through early 2012). So if this outreach happened as the emails suggest, it raises a pretty basic due-diligence question that every nonprofit understands when it’s convenient: what vetting is actually happening when institutions solicit major gifts—and what gets waved through when the potential donor is rich enough?

Which brings me to the thing our industry hates saying out loud: theatre is phenomenal at calling something “complicated” when what we really mean is “useful.” We write mission statements like poetry. But when money shows up wearing a tuxedo, we suddenly develop a speech impediment.

Actually, it’s not complicated. It’s not nuanced. It’s not an “everyone makes mistakes” situation. If someone is a convicted sex offender, you should cut ties. You don’t keep the relationship warm. You don’t keep the door cracked. You don’t treat them like a resource. You don’t let their wealth smooth over what should be a hard stop.

So no, the core question here isn’t “what did this person do,” or “did that person know,” or any of the internet’s favorite sloppy little games. The question is what kind of ecosystem keeps making room for the worst people as long as they can write a check—and what it says about the accountability culture New York theatre loves to claim it has built.

And this is where I want to put a pin in it for now, because the Taymor and Horowitz mentions are not the only theatre-adjacent threads sitting in this archive. There are other items. Other names( such as Alan Cumming, Hugh Jackman). Other little “normal” interactions that, in context, stop feeling normal very quickly. I’m going to get to them. But even at this early stage, the larger point is already clear enough to say out loud.

If you’re a cultural leader, if you run a major nonprofit, if you’re one of the people who shapes what gets made and who gets celebrated in New York theatre, then “no comment” is not a values statement. It’s a strategy. And the longer this sits unanswered, the more the industry looks like it’s doing what it always does when money and power are involved: waiting it out until everyone gets bored.

So here’s the ask, and it shouldn’t be controversial: if Julie Taymor, Jeffrey Horowitz, or anyone else whose name appears in these materials had a relationship with Jeffrey Epstein that was purely logistical, incidental, or misunderstood in context, then now is the time to say that plainly. Clarify what the relationship was. Clarify when it ended. Clarify what, if any, safeguards were in place. Clarify what vetting was done, what standards were used, and what would be done differently now.

Because if the theatre world is serious about accountability, it can’t only apply to the people who don’t have access to donors, boardrooms, or institutional insulation. It has to apply up the ladder too. And it has to start with the simplest question of all: why was Epstein still being treated like someone worth accommodating in the first place?