What Theatre Professionals Need to Know About How To Treat Sex Workers

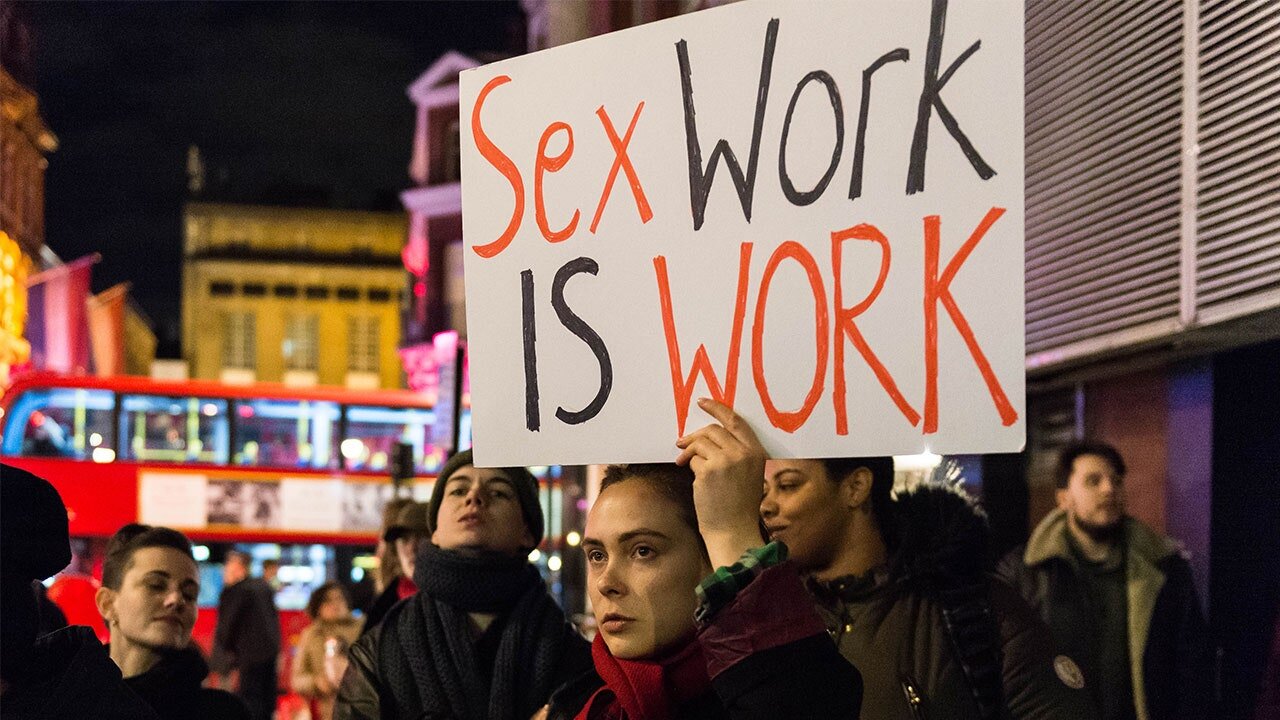

(Photo: Getty Images)

This article was originally published in January, 2020.

It was a fall night during my junior year of college, and one of the male grad students had cornered me at a cast party for whatever show our theatre department had just closed out. He was drunk, I was sober and avoiding the cloud of pot smoke coming from the front deck. I’d hidden in the back of the small apartment, standing in a crowded hallway talking to classmates, when he appeared before me and started in.

“You need to stop this shit and take yourself seriously.”

The “shit” he was talking about was my hobby of doing amateur nights at the local strip club. It was fun, it was empowering, it gave me extra cash. In Montana, $300 was basically rent for the month. Anything above that was gravy.

Never mind the underage drinkers at his home or the illegal drug use going on in full view of the street, he had decided the one person in need of a lecture was me. This man, only seven or eight years my senior, with whom I did not have any sort of close relationship, laid into me about how it was fine for me to be a slut but getting naked on stage for money was wasting my talents as a performer and sullying any good reputation I had.

Needless to say, I never became his friend.

A year later I graduated from amateur night to dancing five times a week at a truck stop. Two years later, I moved to Seattle and diversified my income streams, moving into other forms of sex work. At the same time, I became a burlesque scene mainstay, performed in plays, and started work as a script consultant for playwrights wanting to write about sex work. They said they didn’t know any other sex workers they could talk to, to which I replied that they probably did. That I am hardly out of the ordinary.

While I may be the loudest sex worker many theatre professionals know, I am far from the only one. There’s no way to get accurate numbers regarding how many women have done sex work at some point in their lives, the stigma around coming out is too high to get an honest accounting. But trust me when I say, it’s high. Trust me when I tell you how relieved they were to come out about it to someone who understood not only the risks of revealing their past but also the circumstances around their choice to do that work: the joy, the necessity, the good times, and the bad.

Theatre is supposed to be about sharing stories, but for current and former sex workers in the business, it can be the story that ruins your career.

This is not to say you can’t play a sex worker onstage. From Neil Simon classics to musical theatre to opera to contemporary award winners, there’s no shortage of opportunities for an actress to bare it all for an audience.

And that is why I need everyone in this industry to start caring more about sex workers.

As theatre professionals, we love to applaud ourselves for being progressive. We talk a big game about confronting racism (“Look, we added one show about an African American family to this season!”), transphobia (“We have one ensemble member in one show who is an out trans woman, but golly you wouldn’t know it to look at her!”), sexism (“We gender-swapped an American classic with all white women!”), disability (“We cast an actual blind person as the alternate in The Miracle Worker!”), and almost anything else. Double points if you can use the word "intersectionality" (the belief that different marginalized identities can overlap to create specific kinds of stigma and discrimination) in the program notes.

Do you know what sex work intersects with?

EVERYTHING.

Sex work is a profession where (usually) you are your own boss and set your own hours. Because of this, it is a job that many turn to if they are discriminated against by the traditional workforce. Sex workers vary from highly empowered workers who love every moment to impoverished folks who decided this was the best choice for them to get by.

In many states, it is perfectly legal to fire someone for being trans and there are plenty of studies out there showing the biases that keep women and people of color (and especially women of color) from being hired as often or as lucratively as white men.

In the theatre, we have the ability to create the world we want to see. Yet so many companies want to wallow in sadness or stereotypes about sex work.

Let me tell you a story.

Several years ago I heard that an immersive theatrical production was being put on in my area about a famous red-light district that had existed some 150 years ago in a major American city. It was being produced by a colleague. It was slated to be a politically-minded piece that tackled serious issues, issues that still affect the entire nation today. I was thrilled and immediately tried to be involved, offering myself up as a performer and a consultant. I auditioned but was told advisement wasn’t needed: the cast didn’t need to talk to anyone.

To make a long story short, one of the male cast members went to see a sex worker peer of mine as “research” and stiffed her several hundred bucks. When I told the director this, he compared sex workers to coffee machines. Literally. He said that if someone was doing research as a thief and went to a local coffee shop and stole the espresso machine, it would be exactly the same as this situation. He said this had nothing to do with his production, and informed me that his sitting down with me to listen to my concerns over how the text of the play dealt with sex workers was a "courtesy”.

He did, to his credit, talk to the actor I informed him about. But he said that he wasn’t going to fire this man. The actor's “research” on his off hours was his business and had nothing to do with the production itself. According to this director, what actors do in pursuit of research, even if it’s illegal or immoral, is of absolutely no concern to a production team.

When I calmly asked, “But don’t you think this might have been avoided if you had connected me with cast members hoping for information, as I initially offered?” I was accused of berating my colleague.

I was then not cast in the show as I had been told I would be.

Another story, this one is happier:

Another theatrical production, yet again set in a historical period and focused on a specific famous brothel (this one was more Best Little Whorehouse in Texas meets Mad Men, the other more Pretty Baby). The production staff came to me specifically and asked me to give them notes. They made time to sit down with me and hear my thoughts, even though some of those notes were hard for them to hear.

I was asking them to change things that were precious to them, words they had worked on and workshopped and even put on stage two years prior: historical discrepancies, personal feelings I had, notes that related specifically to the city we were in, and our particular sex worker culture.

Some of the things we argued about went unchanged, but overall these people really wanted to do right by sex workers, even though they were telling a story from the 1960s. They had the knowledge to realize that current sex workers would be attending performances with clients. They realized that the issues covered in their show are issues that still affect the industry landscape of our city today. They realized this show could reach audiences who didn’t know much about the sex industry and might persuade them to be more open-minded about it. They realized that they had me auditioning and wanted to make sure that if any closeted sex workers wound up in the show that they wouldn’t feel disrespected and leave the production resentful.

That is not to say that I was the sole reason they considered these things, simply that at some point they realized that I, an actor they had asked to audition, was also a sex worker and that there might be more sex workers among other actors they had invited, so maybe they should make sure we wouldn’t read our sides and wind up feeling like we were betraying our fellow sex workers by being in this production.

They also allowed the Sex Workers Outreach Project (SWOP) to set a booth in the lobby so that audience members could learn more about how to help sex workers today.

The one thing both of these shows had in common was that the main narrative dealt with corporate management and politicians. Sex workers in these stories were the ensemble or set dressing. But there was a big difference in how they were viewed.

The second show viewed them as an essential voice, as the backbone to this story, even if they didn't have the most lines. When they did speak, they had a variety of things to say—different views on their profession and lives. The first show? Most of the talking was done by men and when sex workers did speak it was stories of abuse and woe.

My notes about this, about sensational storylines like women wanting to murder their clients, about all clients being rapists and all women dreaming of earning enough money to one day quit working and get married, about women having sex with animals, were met with that age-old argument: “It’s historically accurate." But when I pushed to see the source material, I found nuance and joy side by side with brutality and coarseness. The playwright had simply elected to edit the high points out.

You can tell a lot about how someone will view current sex workers based on how they view past ones. All of the historical sex workers are dead and buried, often without having left behind their own words. But today’s sex workers? We have blogs. So many blogs and Twitter accounts and Instagrams straddling the personal and the political. It isn’t hard to come across a sex worker as a real flesh and blood person living in the here and now.

And yet many artists resist this, preferring the romanticized and tragic tales of bygone eras that they can turn into “art”. They don’t care how this affects sex workers today because why would educating audiences or standing by your peers be as important and making something edgy that sells tickets?

This attitude isn’t limited to sex work, of course, but as I said earlier, it often intersects with it. When you think of happy or at least sympathetic sex workers in the media, what do you think of? Julia Roberts in Pretty Woman. Fantine in Les Mis. Belle du Jour in Secret Diary of a Call Girl.

All these women are white. (Fantine doesn’t have to be but she usually is cast as such.) They are all traditionally attractive.

When I think of women of color who are also sex workers in media, I think of nameless bodies in police procedurals and loud-mouthed women shouting at their pimps. Here we have whorephobia (stigma against sex workers) intersecting with misogynoir (racism against black women) to create a double stereotype that pushes the harmful narrative that that black women are overly sexual, poor, and/or “trashy”. They don’t get to be as empowered as their white counterparts, for the most part.

For example, Belle has a black friend for two seasons of Secret Diary named Bambi. Bambi is attractive but deemed “common” by their joint agent and often seen as ditzy comic relief who is not nearly as on top of her shit as the worldly and white Belle.

Even a good example, the one prominent and named black sex worker I can think of, Maeve from Westworld, endures an immense amount of violence. We could talk about robots and freedom and the subversion of dead hooker tropes, but why doesn’t a character like this exist in a story where she doesn’t have to get shot on a daily basis? Why, when we have a smart and capable black sex worker on TV, is she in a sci-fi show about sexual tourism?

In writing this article I asked around for other examples and was given exactly one: a character on The Client List, a show that I had forgotten existed but I’m told was better at representation than one would expect from any TV show, let alone one on The Lifetime Network. So while it is nice to know there is an example out there, it is from a show that doesn’t have the same cultural visibility as other sex worker-centered media. Lifetime branded itself with the slogan “Television for Women” for 18 years (1994-2012), which to many people is shorthand for “not worth my time”.

And that brings us back around to the priorities of theatre. American classics, Shakespeare, and even modern plays are disproportionately focused on men’s stories or have primarily male casts. The theatre and film industries have long demonstrated doubts about whether women-centered stories have broad market appeal. When you start adding in other non-cis male identities, even the most progressive of artistic directors might wring their hands over being accused of tokenism in attempting to be “inclusive” and “representative” while also adhering to the perceived necessities of the bottom line.

But women, all women: trans women, women of color, poor women, uneducated women, empowered women, angry women, people who are not women but were labeled female when they were born and now identify as something else: they are not tokens. And neither are sex workers.

We are here. We have always been here. And I do not just mean in the sense that the histories of sex work and theater are tied together thanks to many actresses in the 1500-1800s also moonlighting as sex workers (apparently the one eternal truth in theatre is that it’s impossible for 90% performers to make a living on stage). I do not mean in the sense of a snide remark that an actress you personally dislike must have visited the casting couch to get work. I mean that the person sitting next to you in the lobby, standing next to you at rehearsal, or across from you at that audition table is or was a sex worker.

And it’s time you included every sordid, scandalous, surprisingly boring bit of us in your productions.

Maggie McMuffin is an actor, nightlife performer, and children's party clown who can be found on most social media. www.maggiemcmuffin.com